Caixabank (Go to Home)

Caixabank (Go to Home)Income inequality improves in Spain

Inequality report by CaixaBank Research.

Inequality report by CaixaBank Research.

- The main factors helping to push down inequality are a strong labour market and, in particular, a steadily falling unemployment rate.

Economic growth has been inconsistent in recent years. In the space of just five years, we have witnessed five big shocks back to back: the pandemic, severe global supply chain disruptions, the energy crisis, an inflationary shock and rising interest rates. Each of these shocks, aside from affecting economic activity overall, could have very severe consequences for the most vulnerable segments of the population. Inequality increased significantly during the pandemic, so what has happened since then? Among the developed countries of the world, data is available up to 2022, and in most of it inequality continues to show a long-term upward trend. However, for Spain we have data up to November 2024 and fortunately, the story is very different.

During the pandemic, CaixaBank Research developed an indicator to track the course of income inequality in real time. Since then, it has continued to be updated monthly on the website . More precisely, the trend in the millions of salaries that customers pay directly into their accounts with CaixaBank (duly anonymised) is analysed each month, along with social security payments received as unemployment benefits or under furlough schemes. All this information is processed using big data techniques to construct the main inequality indicators.

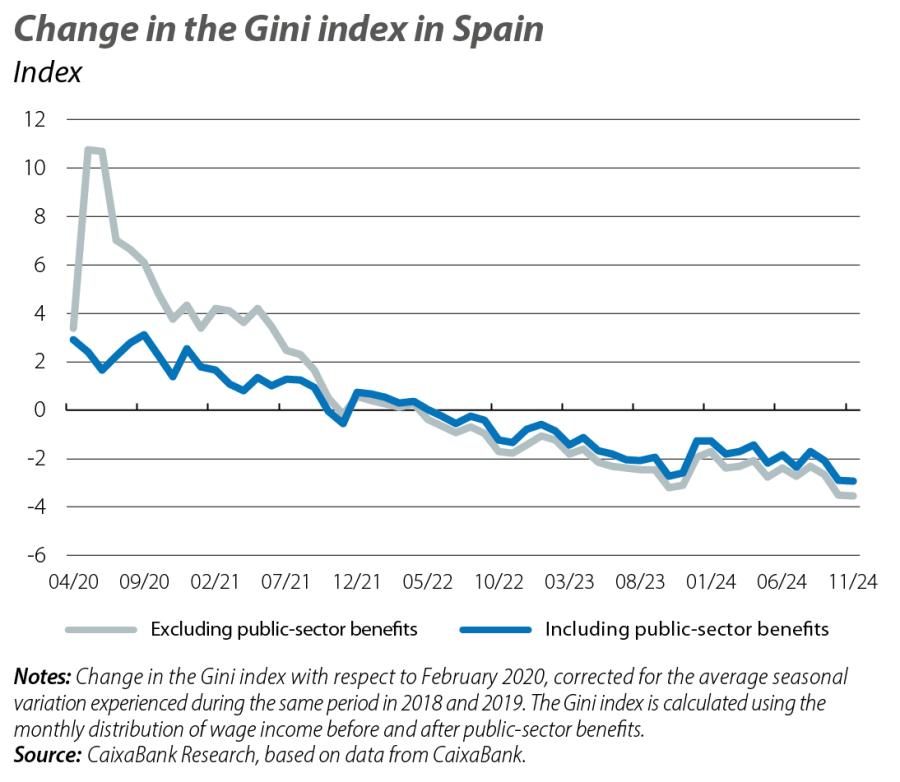

During the pandemic, a sharp increase in wage income inequality could be observed. CaixaBank Research also found that the increase would have been even greater if the various support programmes had not been implemented. The Gini index calculated without taking into account public sector transfers increased by more than 10 points between February and May 2020. However, when public sector transfers are taken into account, the increase was much lower, at 2.3 points for Spain as a whole over those same months.

Diversity by age group, origin and territory

One of the monitor’s strengths is its high granularity, which allows us to analyse the trend in inequality by age group, origin and also across the various autonomous regions of Spain. This made it possible to see the varying impacts of the pandemic in all these areas. For example, the most affected groups were younger people and people born outside Spain. Geographically, we saw how the autonomous regions in which the leisure and hospitality sectors are more prominent, such as the Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands, were more heavily affected. However, in all these cases the mitigating impact of public sector transfers played an important role.

Since then, inequality has fallen sharply. In 2022, various indicators that track income inequality were already at pre-pandemic levels. The CaixaBank Research indicator anticipated this at the time, and the data that has now been published have corroborated it, thus making the metric even more reliable.

Levels prior to the pandemic

Since 2022, CaixaBank Research’s real-time indicator shows that inequality has continued to trend downward, both in Spain as a whole and also between different groups and geographical areas. Specifically, for Spain as a whole, in November the Gini index was already 2.9 points below pre-pandemic levels. While the decline by age paints a similar picture, the reduction in inequality among those born outside Spain is noteworthy, as it is now 3.8 points below pre-pandemic levels. Geographically, those autonomous regions in which the tourism sector is significant such as the the Balearic and Canary Islands, have achieved reductions in inequality of over 4 points.

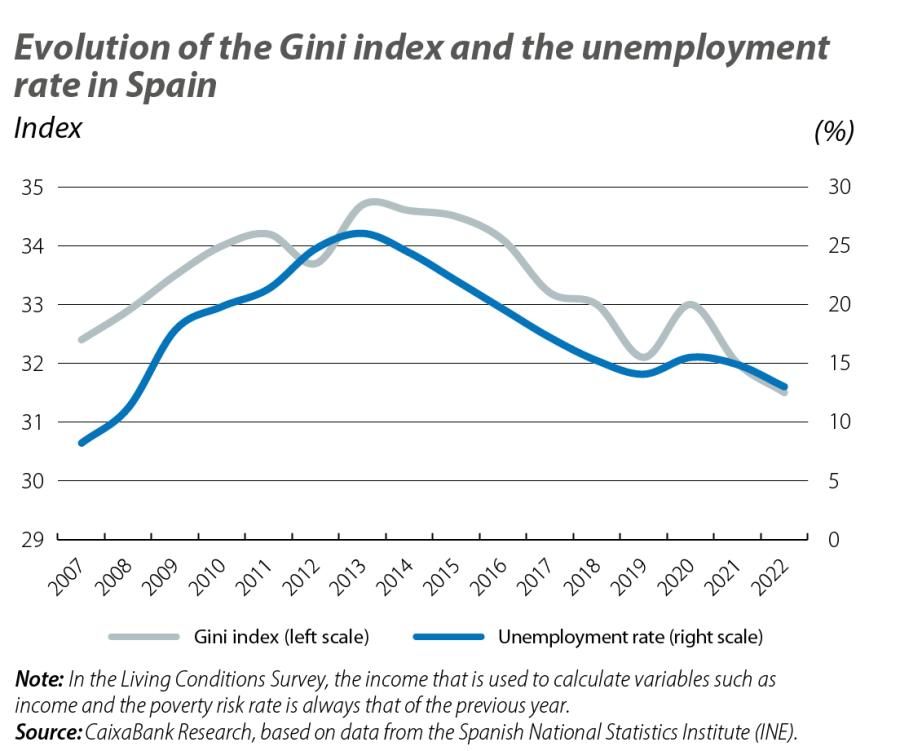

There has been a significant decline in inequality in recent years. This is evident when we examine the trend in the Gini index from a historical perspective or when we compare its levels across different countries.

The Gini index tends to be fairly stable over time. For example, in Spain, between 1990 and 2019, it fell by 1.9 points. In the United States, one of the countries where inequality has increased the most, the Gini index rose by 3.5 points during this same period. In view of Spain’s strong performance in recent years, it is likely that when the data for Germany and France are released, it will show that the gap between Spain and these countries, in which the Gini index was 2.5 and 2.9 points respectively below that of Spain in 2019, has narrowed significantly.

The main factors that are helping to push down inequality to fall are a strong labour market and, in particular, a falling unemployment rate. The relationship between the two variables is very close. Given that the difference between being out of work and earning an income from work is significant, reducing the unemployment rate becomes the key variable in bringing down inequality. Notably, during the pandemic, 90% of the changes in the Gini index are down to movements in the unemployment rate.

As long as the Spanish economy is expected to continue growing in the coming years and the unemployment rate continues to fall, inequality should continue to trend favourably.

Read the report ‘Spain in front of the mirror: the evolution of inequality and the middle class’